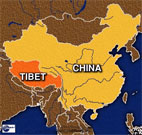

Tibetans retain identity 50 years into exile

Dharamsala, India - Two callow Tibetans waited this month outside the Tibetan Reception Centre, which receives new refugees from Tibet, on one of the main streets that runs through McLeodganj, a suburb of Dharamsala, nestled near the edge of the snow-capped Dhauladhar range.

Dharamsala, India - Two callow Tibetans waited this month outside the Tibetan Reception Centre, which receives new refugees from Tibet, on one of the main streets that runs through McLeodganj, a suburb of Dharamsala, nestled near the edge of the snow-capped Dhauladhar range.

Their weather-beaten faces betrayed their arduous journey to McLeodganj, where Tibet flags adorned with snow lions flutter at key intersections.

Coming from the Kham region in eastern Tibet, the two trekked Himalayan passes and took a vehicle to Nepal's Kodari area before reaching India's Dharamsala, known as "Little Lhasa" because of its large population of Tibetan refugees.

Casting furtive glances at passers-by on the street and sharing a joke, they were still oblivious to a life in an alien land and the pain of a stateless identity.

The new arrivals prepared for registration, which involves giving a first-hand account of their life and journey to India, after which they are sent to Tibetan settlements across India.

Ten years ago, Lhugar Jam made it to the same street as a refugee.

Now a 34-year-old researcher on Tibet, he said he thinks it was a good decision to leave his homeland because the repression of the Tibetan community by Chinese authorities is systematic and opportunities are limited. A common aim among Tibetan youth is to be a truck driver.

Many in the Himalayan region, the highest on Earth, do not have access to traditional education, are far-removed from their culture and speak better Chinese than Tibetan.

Jam is among the 110,000 Tibetans who followed the Dalai Lama to India - the largest concentration of Tibetans outside Tibet - where they are housed in 35 settlements.

Since the Dalai Lama fled Tibet 50 years ago on March 17, 1959, he has overseen a flourishing Tibetan Buddhist culture and religion in India as monasteries teem with monks and Tibetan schools impart grounding in Tibetan traditions and language along with modern education.

"Although Indian authorities had offered mainstream schools for Tibetan children, the Dalai Lama wanted separate schools so they could grow as Tibetans and the responsibility of the Tibetan struggle could be passed on to them," said Karma Yeshi, a member of the Tibetan Parliament-in-exile.

"The preservation of Tibetan identity and culture is indeed the biggest achievement of the Tibetan government," he said. "This has enhanced political consciousness in our community to challenge Beijing."

Exiles said Tibet is more alive here than in Tibet, where there are restrictions placed on monks joining monasteries. Earlier, monks used to go to Lhasa to study Buddhism but now such centres are mostly in India.

"We have utilized resources not for buying arms but for education," said Ngawang Woebar, president of Gu-Chu-Sum, a group of former political prisoners, who fled to India in 1991. "I think our movement will sustain not only because of China's wrong policies but because we have strengthened our education and built the community in India. Retaining our Tibetanness is central to retaining our struggle and the desire for going back."

In the past 50 years, the Tibetans were also forced to be exposed to the world and their isolated Shangri-la was demystified. A renaissance in Tibetan Buddhism during the same time ensured there is not a single country where its culture and religion have not reached.

A high-level of democratization was also achieved in the community in India, under which even the authority of their living god, the Dalai Lama, can be divested by a two-thirds vote of the Tibetan Parliament.

"Now Tibetans are greatly conscious of keeping their identity," Woebar said. "Though many are eligible for Indian citizenship, they prefer not to."

The pitfall of this insular nature is that the Tibetans have little visibility within India. They are not able to establish a connection with the locals, who do not understand their aspirations.

At the same time, there are concerns about unemployment, limitations such as those on property ownership, and gaining processional education and jobs with good pay because few positions are reserved for Tibetans in institutes of higher learning.

There is also the threat of younger Tibetans drifting away from the community as many venture alone to take up jobs in Indian cities as call-centre employees or settle in Western countries.

B Tsering Yeshi, who is in her early 50s, belongs to a different generation from the young refugees in McLeodganj and Jam. She has spent her entire life in exile, and her dreams of returning have faded.

"I grew up in India but never thought I belonged here, like the many Tibetans who don't speak Hindi or build houses here," Tsering, president of the Tibetan Woman's Association, said with a faraway look in her eyes. "There is no sense of belongingness."

"All my life, I have pined for returning to my roots and the feeling of homecoming," she said. "It is painful. I was born stateless, grew up stateless and will die stateless." (dpa)