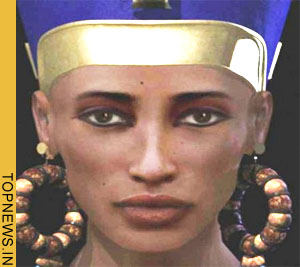

Nefertiti's "hidden face" proves Berlin bust is not Hitler's fake

Hamburg - Using 21st Century medical computer technology, German researchers have unveiled the "hidden face" below the surface facial features of the famed bust of 18th Dynasty Queen Nefertiti - dispelling once and for all nagging rumours that the bust might be a duplicate made at the orders of Adolf Hitler in the 1930s, and that the genuine bust was lost in the chaos following World War II.

Hamburg - Using 21st Century medical computer technology, German researchers have unveiled the "hidden face" below the surface facial features of the famed bust of 18th Dynasty Queen Nefertiti - dispelling once and for all nagging rumours that the bust might be a duplicate made at the orders of Adolf Hitler in the 1930s, and that the genuine bust was lost in the chaos following World War II.

The researchers from Berlin's Imaging Science Institute at Charite Hospital made a series of CT scans of the bust and confirmed findings of a less sophisticated CT scan 17 years ago which revealed that the sculpture has a limestone core and is covered in layers of plaster-like stucco, called "render" by Egyptologists.

That finding was not new. But what was new is the fact that the new CT scan revealed that the limestone core was carved with such artistic precision that it forms a veritable inner copy of the outer face.

Now the Berlin experts are wondering whether the original artist originally carved the bust in limestone, but then changed his mind and added a plaster glaze which gave the queen softer and more rounded features. The experts say the limestone facial features are a bit more angular.

It is a question which may never be answered. But the latest CT scan does answer the lingering question as to whether the bust, which forms the cornerstone of Berlin's Egyptian collection, is genuinely 3,300 years old - or whether it is a fake made 70 years ago as part of a scheme by the Nazi fuehrer to assuage Egyptian ire by giving them a fake bust of Nefertiti, while Hitler kept the original for his own private collection.

No 20th Century artist would go to the extraordinary trouble of carving a limestone bust in exquisite detail and then hiding it below a coat of plaster. For years, the Berlin officials have argued that chemical tests showed the paint and plaster on the bust were identical to those used by Ancient Egyptian artisans. Now they also have computer-backed evidence that the limestone carving is also genuinely ancient.

Egypt has demanded the return of the bust since it went on display in 1923 in Berlin at the height of worldwide "Egypto-mania" in the wake of the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen by Howard Carter.

The painted limestone and plaster bust, depicting the elegantly chiselled life-sized features of a stunningly beautiful woman wearing a unique cone-shaped headdress, has been the pride of the collection since German archaeologists discovered the bust in the ruins of an ancient artist's studio on the banks of the Nile in 1912.

An alluring mystery has surrounded the bust since its discovery on December 7, 1912, incredibly intact and sporting vibrant colours, after lying forgotten in the sands since the tumultuous close of the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaton, one of the most enigmatic rulers of all time.

In 1913, the Ottoman Empire agreed to allow its finders, part-time German-Jewish archaeologist and full-time entrepreneur James Simon and his Prussian colleague Ludwig Borchardt, to retain possession of the bust.

The simmering controversy between Egypt and Germany boiled over anew earlier this year when a German news magazine printed excerpts from documents which allegedly indicated Borchardt deliberately used subterfuge to "smuggle" the bust out of Egypt. The documents are not new to scholars, however, who say Borchardt and Simon did not need to be devious. Instead, the Ottoman Empire officials simply failed to appreciate the artistic value of the artefact.

Despite persistent rumours that Borchardt and Simon smuggled out the bust under a coating of mud, the plain truth of the matter is that Ottoman authorities failed to recognize the bust as a masterpiece. In those days, the stark style of the Amarna Period was not deemed as valuable as the more traditional styles of other periods.

Borchardt and Simon, however, immediately recognized the bust's appeal to European tastes for Art Nouveau and other post-Victorian styles. They did indeed breathe a sigh of relief when the Ottoman authorities blindly gave their stamp of approval to their request for removal from Egypt.

Borchardt and Simon carted it off to Europe where Simon displayed Nefertiti prominently in his home in Berlin before later lending it to the Berlin museum and finally donating it to the Berlin collection in 1920.

The discovery of Tutankhamen's tomb in 1922 spawned an Egypto-mania craze as well as the Art Deco style. King Tut's treasures flaunted the "decadent" style of the late 18th Dynasty, and Nefertiti suddenly was a fashion trend-setter.

Crowds flocked to the Berlin museum to see Nefertiti and shame-faced Egyptian authorities realized they had made a ghastly mistake a decade earlier.

"They suddenly realized that this bust, which had been dismissed as 'un-Egyptian' in 1913, was in fact one of the most exquisite examples of Egyptian art," the Berliner Zeitung newspaper quoted one expert as saying.

In 1933, the Egyptian government demanded Nefertiti's return - the first of many such demands over the ensuing decades. One of the many titles Hermann Goering held was premier of Prussia (which included Berlin) and, acting in that capacity, Goering hinted to King Fouad I of Egypt that Nefertiti would soon be back in Cairo.

But Hitler had other plans. Through the ambassador to Egypt, Eberhard von Stohrer, Hitler informed the Egyptian government that he was an ardent fan of Nefertiti:

"I know this famous bust," the fuehrer wrote. "I have viewed it and marvelled at it many times. Nefertiti continually delights me. The bust is a unique masterpiece, an ornament, a true treasure!"

Hitler said Nefertiti had a place in his dreams of rebuilding Berlin and renaming it "Germania".

"Do you know what I'm going to do one day? I'm going to build a new Egyptian museum in Berlin," Hitler went on.

"I dream of it. Inside I will build a chamber, crowned by a large dome. In the middle, this wonder, Nefertiti, will be enthroned. I will never relinquish the head of the Queen."

While he did not mention it at the time, Hitler envisioned more for the museum. There was to be an even larger hall of honour, with a bust of Hitler.

It was rumoured immediately after World War II that Hitler had commissioned a copy of the bust for possible handover to the Egyptians after a Nazi victory. American Allied art experts claimed they found two wooden crates in a salt mine south of Berlin where the German capital's museum art treasures had been placed for safekeeping during bombing raids. The two crates allegedly contained identical Nefertiti busts.

But in post-war confusion, one of the crates got lost. The whereabouts of the "other Nefertiti" are unknown - assuming it ever existed to start with. From time to time over the years, there have been reports suggesting that the fake bust survived and that the genuine bust is lost. A recent documentary on Germany's ZDF television network revived that theory.

And that is where the new CT scans come to the rescue. They prove once and for all that the bust on view in Berlin is indeed genuine. Whether there ever was a duplicate is now a moot point.

The exquisite limestone bust of Queen Nefertiti forms the focal point of the Berlin collection, which ranks among the top two or three collections in the world outside Egypt itself. The British Museum, the Louvre in Paris and the Metropolitan in New York are the only chief rivals to Berlin's collection, which spans all eras from the pre-Dynastic period all the way through to Roman times.

Hitler's dreams of a monolithic new Egyptian museum never materialized. Instead, Nefertiti will move into permanent quarters in Berlin's Neues Museum later this year, following painstaking renovation work to erase wartime damage.

Ironically, it will be the first time since 1939 that the entire Berlin Egyptian collection will be housed in one permanent location.

Hitler and his mad dreams are long dead. But Nefertiti continues to smile serenely. As she has for 3,300 years. As if to say: "This too shall pass. And I shall endure." (dpa)