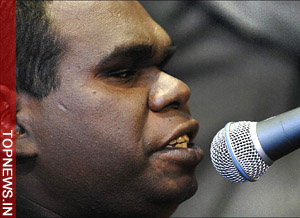

Angel-voiced Gurrumul gives black Australia a gospel

Sydney - It has been hailed as the greatest voice ever recorded in Australia: plaintive yet uplifting, keening but controlled, distinctive but not so extraordinary that it quickly becomes tiresome.

Sydney - It has been hailed as the greatest voice ever recorded in Australia: plaintive yet uplifting, keening but controlled, distinctive but not so extraordinary that it quickly becomes tiresome.

It belongs to blind-from-birth Aboriginal singer-songwriter Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu, and it's about to go global with the release in the United States of the self-titled album Gurrumul, which has done so well elsewhere.

Gurrumul has won every musical honour his country can offer, his first solo album is riding high in the charts and there is the notion that changing times suit this shy and perverse 38-year-old.

"Ostensibly a gentle, country-tinged folk album, this 12-track release is in fact so much more than that and means so much more than that, arriving as it has in the year that the Australian government finally said sorry to our indigenous people and in the same breath as a black man took his place in the White House and in history," music reviewer Tracey Grimson said.

Comparisons with a Bob Dylan or a Barack Obama, a Miriam Makeba or a Woody Guthrie, are unhelpful in unravelling the appeal of someone so divorced from the political world and so caught up in a place few will ever visit.

Gurrumul is a multi-instrumentalist who toured for a decade with the rabble-rousing Aboriginal supergroup Yothu Yindi, but his songs today are sparse and exclusively about the day-to-day life in his Elcho Island home.

He listens to Dire Straits, Neil Diamond, Elvis Presley and the Eagles, but there's nothing derivative in his repertoire and no showmanship in his performances.

"He's not another Aboriginal musician singing protest songs against a rock, reggae or folk-country backing," veteran music industry journalist Bruce Elder said. "Rather, he's a deeply traditional man with a voice of an angel singing of his love of country, his deep spiritual connection with the land, the death of his father, the difficulties of being born blind - which he sings in a mixture of local language and English - and the importance to his life of continuity and his ancestors."

Aboriginal acts haven't succeeded abroad because their songs of protest are marooned in the parochial. Their very exoticism has proved a turn-off.

Yet Gurrumul, who barely speaks English and sings almost exclusively in Aboriginal languages, has broken through by adopting the style of the classic singer-songwriter.

"You imagine Aboriginal music and you imagine didgeridoo and clap sticks, but Gurrumul's a contemporary Aboriginal man," said Michael Hohnen, Gurrumul's manager and record producer. "What you see is a man in black jeans and shirt just singing beautiful songs with an acoustic guitar, and they love it."

Hohnen, who accompanies Gurrumul on acoustic bass on stage and in the studio, is also the principal helper on tour for a man who hasn't learned Braille, doesn't have a guide dog or even a stick.

"Getting in and out of airports with a double bass and a blind musician is quite a challenge," Hohnen quipped.

Gurrumul, who lets Hohnen do the speaking, sometimes replies to questions by e-mail.

Asked by Elder where his inspiration comes from, Gurrumul replied: "I just hear all the sounds. The birds. People talking. The waves. Everything. Sometimes at home I listen to the bungul djama [ceremonies] or the old people talking, and I learn from that way. I listen to radio and CDs all the time. I listen to things because I can't see them. That helps me see what's going on."

It was Elder, the music critic for The Sydney Morning Herald, who described Gurrumul's as the greatest voice Australia has ever recorded and said his work was a mixture of gospel, folk and soul that "reached into a wellspring so deep it transcends cultural barriers."

For fellow music reviewer Grimson, Gurrumul's appeal lies in the authenticity of his work.

"Gurrumul has managed to achieve what all great singer-songwriters must if they are to succeed - he's pulled a curtain from a window and allowed us to peek into a series of intensely intimate experiences and relationships, showing us into this man's most private world," she wrote.

"He's made the personal truly universal, so much so that we don't even need to understand the words to empathize with the chapters in the man's story." (dpa)