China-Dalai Lama talks stall amid tough rhetoric

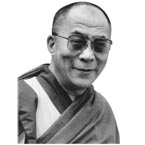

New Delhi/Beijing - The Dalai Lama and China's ruling Communist Party both said they want to reach an agreement on Tibet's future through dialogue, but signs of genuine accord are as elusive as ever, 50 years after Tibet's religious leader and 100,000 of his supporters fled into exile.

New Delhi/Beijing - The Dalai Lama and China's ruling Communist Party both said they want to reach an agreement on Tibet's future through dialogue, but signs of genuine accord are as elusive as ever, 50 years after Tibet's religious leader and 100,000 of his supporters fled into exile.

After Communist Party officials met the Dalai Lama's envoys for the most recent of seven rounds of talks in Beijing in November, China said "serious differences" remained.

It accused the Dalai Lama - who left Tibet on March 17, 1959, in the wake of a failed uprising against Chinese rule - of failing to honour promises made by his envoys at earlier talks in July.

The envoys had vowed not to support Tibetan independence, violent opposition to Chinese rule, disruptions to the Beijing Summer Olympics and the India-based Tibetan Youth Congress, senior Communist Party official Zhu Weiqui said. China calls the youth group a terrorist organization, but it adheres to non-violence.

"They absolutely forgot to carry out their promise and did not stop boycotting and destroying the Beijing Olympics," Zhu said of the Dalai Lama and his supporters after the November talks.

"Instead, they intensified sabotaging activities and continued to attack the [Chinese] central government," Zhu charged.

The two Tibetan envoys also reported little progress in the talks, telling reporters in Dharamsala, the Indian seat of the Tibetan government-in-exile, that they found an "absence of serious and sincere commitment" from China.

In recent years, the Dalai Lama has adopted a "middle way" by publicly renouncing independence in favour of "meaningful autonomy" for the 6 million Tibetans within China.

China recently reiterated its position that "the door is always open" for talks if the Dalai Lama "stops separatist activities and focuses on improving relationships with the central government."

But remarks by Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi Saturday showed the depth of the gulf between the two sides.

"The Dalai side still insists in establishing a so-called greater Tibet on a quarter of Chinese territory," Yang told reporters.

"They want to drive away Chinese troops from Chinese territory," he charged.

Such rhetoric has hardened the positions on both sides, analysts said.

"Consistent use of intimidating and aggressive language within the Chinese leadership on the Tibet issues has made it impossible for moderate officials to risk expressing views about Tibet that suggest any kind of compromise, so at the moment, any progress [in the talks] is impossible," said Robbie Barnett, an expert on Tibet at Columbia University in New York.

The Tibetan government-in-exile has also hardened its stance, sensing increasing opposition among exiled Tibetans to the Dalai Lama's middle way. Critics of the policy said the movement should demand independence instead of autonomy.

Frustration over the talks with China has even prompted the most moderate of Tibetan exile groups, the Tibetan Women's Association, which had always supported the middle way, to rethink its stand.

"Having a dialogue is useless if China, instead of hearing us, routinely makes allegations against His Holiness and carries out a cultural genocide," said B Tsering Yeshi, the association's president.

"It is forcing Tibetan organizations to demand independence," Yeshi said.

"If I am never to return and die in India, I'd rather die dreaming of an independent Tibet than a Tibet under China," she added.

Samdhong Rinpoche, prime minister of the Tibetan government-in-exile, said it was open to more talks only if China agrees to discuss a memorandum presented by the Tibetan side that articulated the concept of autonomy for Tibetans.

"There has been no contact since November," he said. "... We do not believe there is any seriousness on the part of the Chinese leadership.

Many observers said they believe the lack of progress in talks on Tibet's future are a major cause of the frustration and tension that boiled over in last year's anti-Chinese protests in dozens of Tibetan areas of China.

In his Tibetan New Year's message in late February, the Dalai Lama talked of "hundreds of Tibetans losing their lives and several thousand facing detention and torture."

He said Chinese authorities intended to "subject the Tibetan people to such a level of cruelty and harassment that they will not be able to tolerate and thus be forced to remonstrate."

Shi Yinhong, an expert in international relations at People's University in Beijing, said he believes the Dalai Lama knows his demand for a "high degree of autonomy" for a group of all Tibetan areas of China would be impossible for China to accept.

At the talks last year, the Dalai Lama's envoys sought Tibetan areas of four provinces surrounding China's Tibet Autonomous Region to be included in any autonomy agreement.

Only about 2 million of China's 6 million Tibetans live in the Tibet Autonomous Region.

"The essence of his proposal can be regarded as Tibetan de-facto independence, overthrowing the fundamental political status in Tibet," Shi said in a commentary for the official China Daily newspaper.

Barry Sautman of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology saw intransigence on both sides.

"There are people in both camps who don't want the dialogue to succeed, and it will go nowhere without the Dalai Lama acknowledging that Tibet is legitimately part of China," Sautman said.

"If he does so, it's possible for religious and cultural autonomy in Tibet to be expanded," he said of the 73-year-old leader.

"The odds are that (Communist) China will outlive the Dalai Lama, a fact that he must become convinced of in order for actual negotiations to be possible," Sautman said. (dpa)