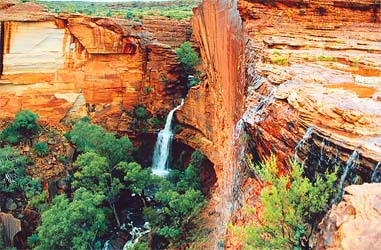

King's Canyon, in Australia's outback, worth getting up early for

Alice Springs, Australia - It is only 6:40 am, but the day's first tour buses have long arrived. You have to get up early if you want to see King's Canyon in the best light. The reds, oranges, yellows and ochers of its sheer sandstone faces are especially vivid just after sunrise.

Alice Springs, Australia - It is only 6:40 am, but the day's first tour buses have long arrived. You have to get up early if you want to see King's Canyon in the best light. The reds, oranges, yellows and ochers of its sheer sandstone faces are especially vivid just after sunrise.

The best-known canyon in the outback of central Australia, King's Canyon, part of Watarrka National Park in the Northern Territory, is a popular destination for tourists who want to take a side trip on their way from Alice Springs to Ayers Rock. Many of them enter the canyon and marvel at the 270-metre-high cliffs from the bottom. But it is more interesting to hike around Rim Walk at the top.

"Welcome to Cardiac Hill," says the grinning tour guide, pushing back his hat. That is what the locals call the steep climb to Rim Walk: an elevation gain of some 100 metres over a short distance. This is another reason to visit King's Canyon in the morning. It is often hot in the afternoon, particularly in the summer months of October through April, when innumerable flies try to crawl into visitors' noses and ears.

The ascent turns out to be less strenuous than expected. The path is paved and well marked. And in case of an emergency, you can call park rangers with one of the four telephones along Rim Walk.

On the western edge of the George Gill Ranges, King's Canyon has rock strata up to 440 million years old. The canyon began as a small fissure in the rocky plateau some 20 million years ago. Wind and rain made the crack ever wider.

The most recent major rockslide occurred at the north face in the 1930s. Some of the boulders in the canyon are bigger than terraced houses. They cannot all be seen up close because some places inside the canyon are sacred to the Luritja - the aboriginal people who have lived in the region for thousands of years - and accessible only to those familiar with their rituals.

There are no such restrictions along Rim Walk. The hike takes a good two and a half hours, and some of it is near the edge of the precipice. The terrain is not for people prone to dizziness or fear of heights.

Sweat pours from the hikers' brows, but there is always something interesting to discover. Some of the rock formations have names. The Lost City, for example, looks a little like large stone beehives. They trap heat between them. The Garden of Eden has a permanent ice-cold waterhole surrounded by vegetation.

The canyon is not named after an English king, which one might expect in Australia. English-born Ernest Giles, who explored the area as the first white man in 1872, named it after Fieldon King, the principal sponsor of his expedition. In any event, whoever climbs back down to the car park, where the tour buses wait with their air conditioning switched on, feels a little like a king. The next tourist destinations beckon, usually Alice Springs or Ayers Rock.

This part of the outback is tame. All of the roads are paved with asphalt, including the one to King's Canyon. And there has been a speed limit of 130 kilometres per hour outside built-up areas since the beginning of 2008.

Some of the traffic signs at intersections in the middle of nowhere seem downright strange. Motorists are reminded to drive on the left side of the road, as though they had just crossed the border into Australia. And they are warned that ignoring a red light is prohibited in the Northern Territory, too, even though the next opportunity to do so is more than 300 kilometres away.

There is one place on the way to Alice Springs that tourists should not miss, namely Stuarts Well Roadhouse, where Dinky the singing dingo awaits an audience. The Australian wild dog was raised by the roadhouse's owner, Jim Cotterill, whose daughters earlier took piano lessons. Dinky likes to jump up on the old piano in the guest room, tap the keys and howl. (dpa)