Biden calls on Europe to put its men where its mouth is

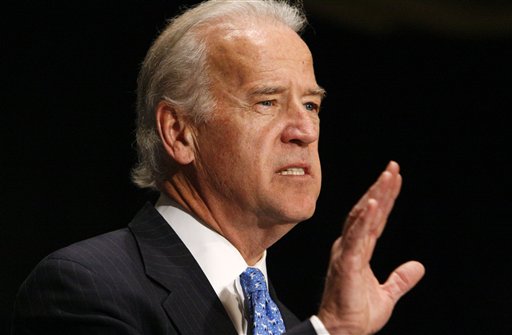

Munich - The US policy of taking world events into its own hands was officially buried by US Vice President Joe Biden in a major policy speech Saturday before the Munich Security Conference.

Munich - The US policy of taking world events into its own hands was officially buried by US Vice President Joe Biden in a major policy speech Saturday before the Munich Security Conference.

Now it remains to be seen whether the United States will follow through on its promises to consult with its allies and talk with its enemies - and how European leaders will cope with a world where they are expected to provide not just counsel, but also the manpower to turn their policy proposals into reality.

"America will do more," said Biden, to the delight of most of the European leaders present at the annual conference. "The bad news is that America will ask for more from our partners as well."

That could mean expectations that European countries will take in Guantanamo detainees released if US President Barrack Obama closes the facility as promised. It could mean calls for more European troops in UN-mandated operations in Afghanistan.

It will also certainly mean US expectations of European support for yet more sanctions on Iran should that nation not open up its nuclear programmes to weapons inspectors.

Any one of those issues by itself could prove a tough nut for European politicians to crack.

Should the United States call on its European allies for help in all of these issues - let alone for unknown threats lurking on the world stage - some leaders might soon find a touch of nostalgia for the days when they were neither consulted, nor expected to contribute.

But first reactions were positive. German Chancellor Angela Merkel welcomed the new US readiness to "work together, not only on analysing challenges, but also in meeting decisions on implementation."

Javier Solana, the European Union's high representative for foreign aid and security policy, was likewise optimistic. "I don't think it's bad news," he said. "We have to put our contributions forward. We cannot be players and not put anything in the basket."

Nonetheless, the newfound US openness may not prove popular in all corners. Biden made a point to reiterate the president's pledge to extend an open hand to any nation that unclenched a fist, a by now familiar reference to Iran.

But on Friday, the speaker of Iran's parliament, Ali Larijani, said that Iran would only consider the new US approach if Washington was prepared to acknowledge past wrongs against Iran.

Similarly, Biden's promise of more openness with Russia regarding proposed missile defence facilities in Poland and the Czech Republic - a move that had been anticipated given the Democrats' scepticism toward missile defence - was pre-empted by comments from Russian Deputy Prime Minister Sergei Ivanov on Friday night.

Ivanov made it clear that the only acceptable solution was a world without those systems in Eastern Europe.

Nor did Biden's speech rule out the possibility of US unilateralism in times of need.

"We'll work in a partnership whenever we can," he noted.

That, in itself, is not a problem, said Karsten Voigt, coordinator for German-American cooperation with the German Foreign Ministry.

"That's the difference between a world power and a country like Germany," Voigt told Deutsche Presse-Agentur dpa, philosophically.

Countries with limited military power, like Germany, must rely on multilateral organizations to achieve their ends. A defence giant like the United States will always keep the unilateral option in its back pocket, he noted.

Voigt instead focused on the positive.

"It was a speech that showed that Europe and America will confront the global and regional problems together," he said. "That we have a level of balance. That there is now a give and take."

The main problem he sees is that so many of the major issues facing the United States lie outside Europe, whereas the partners from whom it seeks help are predominantly within Europe. That could mean that, even if European allies are willing to lend aid, practical considerations might limit their ability to do so. (dpa)