Sixty years on, Germany faces up to new economic challenges

Berlin - With Germany engulfed by a deep recession, it could be tempting to hope that the nation is once again turning to the economic model that helped forge its economic miracle in the decades after the modern German state was created in 1949.

Berlin - With Germany engulfed by a deep recession, it could be tempting to hope that the nation is once again turning to the economic model that helped forge its economic miracle in the decades after the modern German state was created in 1949.

But, despite the praise heaped on Germany's so-called social market state, which seeks to plot a course between planned economies and laissez-faire markets, the rules of the modern German economic game have drastically changed in recent years.

What is more, this comes as Europe's biggest economy is forced to face up to new challenges. Recently, the German government had to pump more than 80 billion euros (109.4 billion dollars) into the nation's economy to try to haul it back onto a growth path.

At the same time, the scale of the economic downturn might have triggered a new push to extend the country's welfare state, built up under the social market model. Conversely, that put tough structural reforms on the back-burner.

But Germany's membership in Europe's common currency means that, in reality, key parts of the nation's economic management are no longer solely in the hands of German policymakers.

"Europe limits the room to move," said ING Bank economist Carsten Brzeski.

Indeed, the European Central Bank is now in charge of Germany's interest rate policy and Berlin has to adhere to the tough fiscal targets set for euro membership, including a requirement that it hold its budget deficit to a strict 3 per cent of gross domestic product.

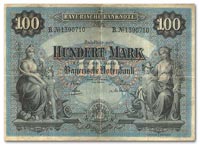

Once a symbol of Germany's post-war economic strength, the nation's beloved Deutschmark was merged with other European currencies to form the euro more than a decade ago.

At the same time, Germany's influential central bank, the Bundesbank handed over its monetary powers to the Frankfurt-based ECB.

But other elements of the old German economic system have continued to serve the country well. For example, close ties between Germany's businesses and banks helped lay the foundations for the nation's post-Second World War reconstruction. The system has proven to be something of a godsend for large parts of German business during the current financial crisis.

It has also helped Germany to largely avoid the credit crunch that has played a pivotal role in the dramatic downward spiral in global growth.

But, instead of drawing on those systems from an earlier era, current economic policymaking in Germany is being shaped by more pragmatic forces.

After all, the calls for extending the social safety net and winding back economic reforms are major debates within the lead-up to Germany's September national election.

Moreover, any additional election spending promises or measures to spur economic growth will eventually run up against the strict 3-per- cent budget rule for euro membership.

In addition, Germany is still struggling with the major shock to its economy caused by the implosion of Communism in the east in 1989 with the resulting enormous costs of sweeping away communist East Germany's bankrupt industrial base. That continues to limit Berlin's room for manoeuvre.

To be sure, two decades after the breaching of the Berlin Wall, parts of eastern Germany remain gripped by mass unemployment and economic despair that means they are likely to be dependent on state handouts for years.

However, it was the tough Agenda 2010 round of labour and welfare reforms launched about six years ago by the former Social Democrat- led government of Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, which appeared to mark out a new economic era for Germany.

"I think the traditional social market economy came to an end with the Agenda 2010," said Brzeski. What is more, despite the recent attempts to back-pedal from the deeply unpopular Schroeder reforms, they were driven by the same forces that are likely to impact the German economy in the future - the greying of the nation's population and globalization.

In the meantime, Germany may also be forced to step back from its dependence on exports as the world's export champion is forced to face a world where slowing economies are weakening demand for German goods.

This, in turn, raises the question of whether Berlin might have to consider winding back taxes - a key source of revenue for the welfare state - to encourage domestic demand to take up the economic slack left by those slowing exports. (dpa)