What environmental changes to expect over next 100 years

Washington, October 8 : A new study has explored how increasing CO2 (carbon dioxide) concentrations may affect trees and water and carbon cycles over the next 100 years.

Washington, October 8 : A new study has explored how increasing CO2 (carbon dioxide) concentrations may affect trees and water and carbon cycles over the next 100 years.

Scientists nowadays face the problem of predicting how each component of our complex ecosystem will respond to the many environmental changes sweeping the globe.

A recent article by Dr. Abraham Miller-Rushing and his colleagues at Boston University has explored how increasing concentrations of atmospheric CO2 may be affecting trees and, ultimately, affecting water and carbon cycles.

It is known that increasing concentrations of atmospheric CO2 affect the physiology and behavior of many organisms, and in plants, changes to the pores (stomata) on the surface of leaves are one example of these effects.

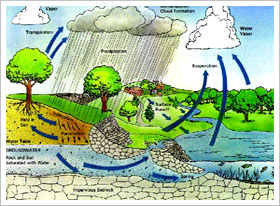

Stomata allow air (containing CO2) to pass into the leaf while water vapor passes out of the leaf. Plants use carbon dioxide to produce sugars during the process of photosynthesis.

With increasing concentrations of atmospheric CO2, stomatal density decreases while rates of photosynthesis increase.

The decrease in stomatal density results in decreased water loss through the leaves.

“These changes in stomatal behavior and water use efficiency can, in turn, have large impacts on plants and can alter ecosystem-scale water and carbon cycling,” Miller-Rushing said.

“For example, soil moisture, runoff, and river flows might increase and drought tolerance in individual plants might improve,” he added.

Miller-Rushing and his colleagues examined the stomatal density on leaves, the length of the cells that surround the stomata (called guard cells), and the leaves’ efficiency of water use (a measurement that compares the amount of carbon that is converted to sugar with the amount that passes through the stomata) in 27 trees growing at the Arnold Arboretum in Boston, Massachusetts for the past century.

By examining several dried specimens from each plant that had been collected over the past hundred years, they were able to assess these characteristics in a temporal framework.

During this period, global atmospheric CO2 concentrations increased by approximately 29 percent.

Miller-Rushing and colleagues found that stomatal density declined while guard cell length increased in oaks and hornbeams, although these changes were not dependent on the magnitude of changes in CO2 concentrations.

Intrinsic water use efficiency did not change significantly over time, suggesting that it may not respond to changes in CO2 concentrations over the lifetimes of individual trees, possibly because of compensating changes in stomatal density and guard cell size.

“This finding may have important implications for models that predict changes in future climate, carbon, and water cycles,” Miller-Rushing stated. (ANI)