Discovery of ion channel upturns age-old model of ear

Washington, Apr 24: Turning all ear-related theories on their head, scientists have found that the ion channels responsible for hearing aren''t located where scientists previously thought.

Washington, Apr 24: Turning all ear-related theories on their head, scientists have found that the ion channels responsible for hearing aren''t located where scientists previously thought.

Researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have claimed that the age-old model to explain how the inner ear translates vibrations in the air into sounds heard by the brain is wrong.

The discovery by Anthony Ricci, PhD, associate professor of otolaryngology, and colleagues, could have major implications for the prevention and treatment of hearing loss.

"I had thought that the channels were in a very different place. This changes how we look at all sorts of previous data," said Peter Gillespie, PhD, professor of otolaryngology at Oregon Health and Science University.

Ricci explained, "Location is important, because our entire theory of how sound activates these channels depends on it. Now we have to re-evaluate the model that we''ve been showing in textbooks for the last 30 years."

Deep inside the ear, specialized cells called "hair cells" sense vibrations in the air, which slightly bend tiny clumps of hairlike projections, known as stereocilia, in the cells.

This movement, according to scientists, opens small pores, called ion channels. As positively charged ions rush into the hair cell, mechanical vibrations are converted into an electrochemical signal that the brain interprets as sound.

But after years of research, scientists still haven''t identified the ion channels responsible for this process.

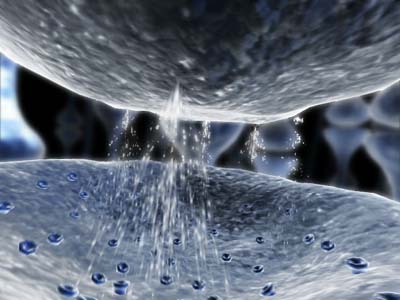

Thus, to pinpoint the channels'' location, researchers squirted rat stereocilia with a tiny water jet. As pressure from the water bent the stereocilia, calcium flooded into the hair cells.

The researchers used ultrafast, high-resolution imaging to record exactly where calcium first entered the cells. Each point of entry marked an ion channel.

To their surprise, the results showed that instead of being on the tallest rows of stereocilia, like scientists previously thought, the ion channels were located only on the middle and shortest rows.

Ion channels on hair cells not only convert mechanical vibrations into signals for the brain, but they also help protect the ear against sounds that are too loud.

Through a process called adaptation, the ear adjusts the sensitivity of its ion channels to match the noise level in the environment.

The findings will appear in the May issue of Nature Neuroscience. (ANI)