Darwin’s view on the origins of chickens was wrong: Study

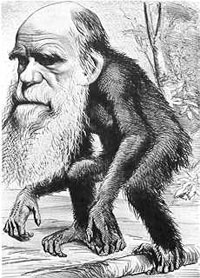

Washington, March 1 : Charles Darwin’s view on the origins of the chicken was not entirely correct, according to a genetic study that has revealed why chickens have yellow legs.

Charles Darwin’s view on the origins of the chicken was not entirely correct, according to a genetic study that has revealed why chickens have yellow legs.

Greger Larson, a Research Fellow at Uppsala University and at Durham University, UK, says that the new study reveals the genetic basis for the appearance of yellow skin in billions of chickens raised worldwide.

In the study report, the authors have revealed that yellow-skinned chickens have a different version of a gene than their white-skinned cousins.

Darwin believed that all chickens came from a wild species known as the red junglefowl. However, when the researchers looked for the yellow-skin gene in the red junglefowl during the study, they only found the genetic variant that codes for white skin.

The researchers revealed that the wild species in which they eventually found the yellow-skin version of the gene was completely different—the grey junglefowl.

“Darwin recognized the importance of studying domestic animals as a model of evolution and this insight has proved enormously influential. The ironic thing is that he believed that dogs were hybrids of several wild ancestors but that chickens only had one, and he was wrong on both counts,” Larson said.

The researcher says that yellow colouring results form pigments found in feed called carotenoids. According to Larson, the gene in question codes for an enzyme that degrades carotenoids into a colourless form.

While white-skinned chickens express this enzyme in skin, yellow–skinned chickens do not express it in skin, allowing the carotenoids to accumulate and produce yellow colouring.

The gene functions normally in other tissues, and yellow-skinned chickens have no general defect in carotenoid metabolism, say the researchers.

“This is a beautiful demonstration of how important regulatory mutations are for evolutionary changes,” said lead researcher Leif Andersson.

“What we are interested in knowing now is why yellow skin in chickens is so ubiquitous. It could have been that yellow skin was perceived to be a marker of health or size or egg production, or it could just be that yellow skin was fun to look at. We’re really not sure. Furthermore, the gene we have identified may be important for carotenoid-based pigmentation in other species like the pink color of the flamingo; the yellow legs of many birds of prey including eagles, falcons and hawks; the pink muscles of salmon, and even skin color in humans,” Andersson added.

The study has been published in the open-access journal PLoS Genetics. (ANI)