Why even treated genital herpes sores boost the risk of HIV infection

London, August 3 : Scientists in the U. S. have made some findings that can explain why an infection that causes genital herpes increases a person's risk of developing HIV infection, even after successful treatment heals the genital skin sores and breaks that often result from herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2).

London, August 3 : Scientists in the U. S. have made some findings that can explain why an infection that causes genital herpes increases a person's risk of developing HIV infection, even after successful treatment heals the genital skin sores and breaks that often result from herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2).

In their study paper, the researchers say that they have uncovered details of an immune-cell environment conducive to HIV infection that persists at the location of HSV-2 genital skin lesions long after they have been treated with oral doses of the drug acyclovir and have healed, and the skin appears normal.

Dr. Lawrence Corey and Dr. Jia Zhu, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and Dr. Anna Wald, of of the University of Washington, jointly led the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)-funded study.

"The findings of this study mark an important step toward understanding why HSV-2 infection increases the risk of acquiring HIV and why acyclovir treatment does not reduce that risk," Nature Medicine quoted NIAID Director Dr. Anthony S. Fauci as saying.

"Understanding that even treated HSV-2 infections provide a cellular environment conducive to HIV infection suggests new directions for HIV prevention research, including more powerful anti-HSV therapies and ideally an HSV-2 vaccine," he added.

According to background information in the research article, HSV-2 is associated with a two- to three-fold increased risk for HIV infection, and that recent studies have shown that successful treatment of such genital herpes lesions with the drug acyclovir does not reduce the risk of HIV infection posed by HSV-2.

The researchers say that they undertook the current study with a view to understanding why this is so, and to testing an alternative theory.

"We hypothesized that sores and breaks in the skin from HSV-2 are associated with a long-lasting immune response at those locations, and that the response consists of an influx of cells that are a perfect storm for HIV infection. We believe HIV gains access to these cells mainly through microscopic breaks in the skin that occur during sex," says Dr. Corey, co-director of the Vaccine and Infectious Diseases Institute at The Hutchinson Center and head of the Virology Division in the Department of Laboratory Medicine at the University of Washington.

The researchers took biopsies of genital skin tissue from eight HIV-negative men and women who were infected with HSV-2. For comparison, they also took biopsies from genital tissue that did not have herpes lesions from the same patients.

Studies conducted in the past have shown that immune cells involved in the body''s response to infection remain at the site of genital herpes lesions even after they have healed.

The current study made several important findings about the nature of these immune cells.

The researchers found that CD4+ T cells-the cells that HIV primarily infects-populate tissue at the sites of healed genital HSV-2 lesions at concentrations 2 to 37 times greater than in unaffected genital skin. According to them, treatment with acyclovir did not reduce this long-lasting, high concentration of HSV-2-specific CD4+ T cells at the sites of healed herpes lesions.

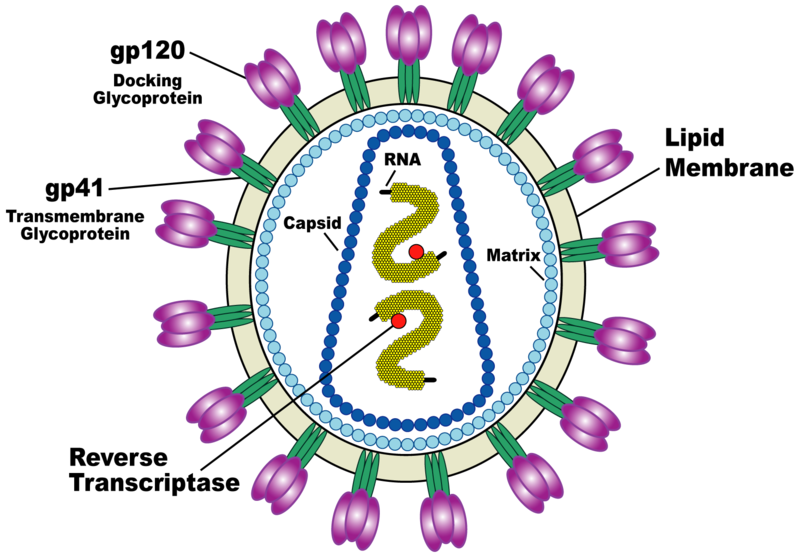

The scientists also found that a significant proportion of these CD4+ T cells carried CCR5 or CXCR4, the cell-surface proteins that HIV uses (in addition to CD4) to enter cells.

The percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing CCR5 during acute HSV-2 infection and after healing of genital sores was twice as high in biopsies from the sites of these sores as from unaffected control skin.

Moreover, the level of CCR5 expression in CD4+ T cells at the sites of healed genital herpes lesions was similar for patients who had been treated with acyclovir as for those who had not.

The team have also observed a significantly higher concentration of immune cells called dendritic cells with the surface protein called DC-SIGN at the sites of healed genital herpes lesions than in control tissue, whether or not the patient was treated with acyclovir. Dendritic cells with DC-SIGN ferry HIV particles to CD4+ T cells, which the virus infects. The DC-SIGN cells often were near CD4+ T cells at the sites of healed lesions-an ideal scenario for the rapid spread of HIV infection.

Finally, using biopsies from two study participants, the scientists found laboratory evidence that HIV replicates three to five times as quickly in cultured tissue from the sites of healed HSV-2 lesions than in cultured tissue from control sites.

They say that all four of these findings help explain why people infected with HSV-2 are at greater risk of acquiring HIV than people who are not infected with HSV-2, even after successful acyclovir treatment of genital lesions.

"HSV-2 infection provides a wide surface area and long duration of time for allowing HIV access to more target cells, providing a greater chance for the initial ''spark'' of infection," the authors write, adding that this spark likely ignites once HIV penetrates tiny breaks in genital skin that commonly occur during sex.

"Additionally, the close proximity to DC-SIGN-expressing DCs (dendritic cells) is likely to fuel these embers and provide a mechanism for more efficient localized spread of initial infection," the authors continue.

The investigators conclude that reducing the HSV-2-associated risk of HIV infection will require diminishing or eliminating the long-lived immune-cell environment created by HSV-2 infection in the genital tract, ideally through an HSV vaccine.

Further, they hypothesize that other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) may create similar cellular environments conducive to HIV infection, explaining why STIs in general are a risk factor for acquiring HIV. (ANI)